I was three when my parents immigrated to the Canadian Prairies from Argentina, having escaped a dictatorial Chile in the hopes of securing a peaceful life for themselves and their children. Though I am myself an immigrant, I find that I identify more closely with first-generation children of immigrants as I arrived so young that I have none of my own memories of Chile. Since I do not speak Chilean Spanish fluently, I never felt that I really fit into the small Chilean/Latin American community that was present in Edmonton. I instead gravitated to others of different ethnicities who were also children of immigrants with similar tenuous connections to their parents’ homeland. Without the constant cultural reinforcement of a large immigrant Chilean community base, I found that my exposure to other Chileans in Canada would often put me in conflict with the expectations of those trying to retain their Chilean identity by holding on to traditions based on memories of home. This experience, this sense of otherness from an early age, was the catalyst for my research into self-identity and how diaspora, trauma, and inherited grief shape it.

I am two. One looks back,

the other turns to the sea.

The nape of my neck seethes with good-byes

and my breast with yearning.The stream that flows through my village

no longer speaks my name;

I am erased from my own land and air

Like a footprint on the sand. [1]

I was twenty-five when I visited Chile for the first time since leaving at six months old. It was years before art school and the voice it would give me. I was adrift and dissatisfied. Looking to make sense of my life I traveled with my father to Chile. My first time outside of Canada since immigrating, I came to realize that I was in search of something that had always seemed to be missing—a sense of belonging somewhere. But when I met my grandparents, and my many relatives, I became achingly aware of how I also didn’t fit into the place of my birth. My parents had always shared warm stories about their life before Pinochet, of being forced to leave their home, and of the hardships of living in Canada. I formed a picture of Chile through them. Confronted with the reality of Chile, I was saddened to discover that I had little real emotional connection to my birth country beyond these half-remembered memories I inherited from my parents. I was missing the fundamental bond that a lifetime of shared experiences and memories instills in families. Without them, I found that I could not connect on any meaningful level with the people that I claim as relatives. Despite my Chilean heritage, and being constantly asked where I was from by the people in Canada, it seemed that my cultural identity was firmly Canadian. Apparently, I had become an Anglo-Canadian ingrained with British-influenced taboos and polite societal conventions. Those filters turned my first adult encounter with Chile into a bewildering experience.

Though the people of Chile were generally welcoming, the prevailing sexist attitudes and the casual racism and homophobia of the time were uncomfortable and surreal.While these things obviously existed in Canada as well, my own negative experiences were few and far between and never so overt. It is hard to put into words the feeling of culture shock I experienced standing on a busy street in the small town of Quillota. In this place where I was born, I watched people who while different, all seemed to share similar physical characteristics. I found it disorientating not to see people of Asian, African, Caucasian, or First Nations ethnic heritage on the busy streets. I felt like I was watching an endless parade of dark haired, medium height, and brown skinned people. The experience of watching what appeared to be an ethnically homogenous group was a revelation. There seemed to be a comfort in the sameness, in the shared customs, the innate understanding of how to navigate that world. As I witnessed the power that comes from the history of place, of hundreds of years of common history, I marveled again at the strength that my parents showed to forge a life in a place as alien to them as Canada. Yet, even here, in my birthplace, as my height and pallor set me apart, I still stood outside. A rock in the stream of humanity that flowed around me.

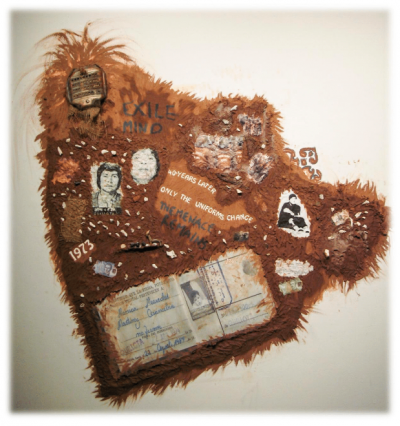

The second time I returned to Chile, I was forty-two. I found Chile a seemingly different place since my visit at twenty-five but also somehow hauntingly the same. I now realize that the reality of a Chile beyond the small town of my birth is complex, as it struggles with issues of immigration, the rights of Indigenous peoples, and the rapid changes to stratified societal conventions as access to technology moves beyond the elite. The constant armed military presence on the streets on Santiago, which was frightening at twenty-five, seemed to have disappeared until you realize that it still teems with uniforms, but they are now Carabineros— members of the police force that have national jurisdiction over Chile. This pervasive presence remains in the day-to-day life—but after over forty years most civilians don’t acknowledge or even seem to see it. I was blindsided by the fact that for others who were born at the beginning of the Coup like me, but raised in Chile, there have always been armed men on their streets. They have never known the horrible disquiet that armed uniforms bring to me, someone who has never been the target of the military or police. How, for me, the constant vigilance of uniformed Carabineros signifies that something is terribly wrong. The potential for violence hovers like a monster at the corner of my eye. The whispers of the dark recollections shared with me by my parents and their friends crawl through my mind as I wait to cross the street beside a quiet sea of brown jackets and tall boots. This fragile veneer of peace breeds in me an instinctual need to not be seen, not trusting this calm at the end of a gun.

But this time I also returned as an artist. An artist who had spent years following the weave of the events that had shaped my life by making works exploring memory, identity, power, transformation, and history. I returned to once again try to create a connection to the land of my birth—this time through art. This time, I came to create work whose seed was generated in the depths of remembrance of the past, the realities of the present, and the unknown of the future. This time, I came with a group of artists from different geopolitical backgrounds and ages. Artists with whom I shared a surprisingly deep commonality of experiences—of displacement, alienation, migration—a CONSTELACIONES to support me to experience the trauma of homecoming to a place that isn’t home.

Since I could not connect to Chile through the shared experience of living through a dictatorship or blood ties, I tried to connect to the landscape, to the earth beneath my feet. Through our intense collaboration, CONSTELACIONES conceived of a journey, a journey that would bring the sculptures that were the catalyst for this return from Santiago to Calama in the Atacama Desert. In Santiago, CONSTELACIONES joined with the people who would witness our return; Dot Tuer, Smaro Kamboureli, Shannon Bell, Jarvis Brownlie, Cassie Scott, Alexei (Lex) Taylor, and Kimberley Wilde. Together we met with our driver Marcelo Andres Valdes Perez to board the passenger van that would drive us and the sculptural forms north to the desert.

We would follow the route of the Caravan of Death with our witnesses—to create art, to offer recognition for those who had passed before us. [2] We travelled through the changing landscape of the coast of Chile, the winter greenery of central Chile slowly giving way the desert colours of the dramatically sculpted northern coast. We shared stories and silences as we drove day after day, the vibration of the van moving down the road settling into our bones. We stopped twice for the night along the way, first in La Serena then in Chanaral and at each of these stops we left a cross form in the sand to mark our passage. At each stop, I felt that I began to ground myself to the land as I breathed in the ocean air and searched the southern stars for familiar constellations.

When we finally reached Calama, CONSTELACIONES, Lex, Cassie, and Jarvis left our rest stop with Marcelo to find the place in the desert where we would set down our sculpture of release following day. This last stop on the journey for the sculptural forms was crucial as here the forms would be left to the wind to become a part of the landscape—an anchored marker of remembrance in a barren ever-shifting space. After a few false starts in that vastness and just as the sun set over the desert, we discovered our spot. A sense of rightness overcame me. Of course, my mind said as the wind blew across my face, this was always the place where the forms should stay, these were always the people who would travel with you to the end of this beginning. This is the place where you belong, in this space of creation with the people who shared the creative labour, the vulnerability, the sheer commitment needed to make this return a reality. This place of belonging is at your core now, nourished by the journey, strengthened by the decisions at every fork in the road, the connections of constellations and the release of the return.

The next day, we were joined by Diana Taylor and Eric Manheimer who flew in to witness the performance. As I took my first step in the laborious procession that marked this performance with the first form cradled in my arms I was overcome with emotion. My mind flew through the memories of all that brought me to this moment, standing under the blinding light on the rock scattered sandy ground of the Atacama Desert. All the intersections of chance meetings, heartbreaking research, weighted personal stories and back-breaking work that lead to this moment in time. As I walked slowly over the uncertain ground towards the distant witnesses waiting for the first form, I began to hum. I began to hum a silly lullaby sang to me by my father after he joined us in Argentina. I hummed what I had come to think of as an unlikely song of defiance, tears coursing down my face. This song sung to soothe a fractious infant by a man unbroken by torments he suffered, by the violence he witnessed.

I hummed this lullaby off and on as CONSTELACIONES laboured together back and forth from the forms we had unpacked and placed on the ground to the mound we were building before the witnesses. Under the punishing sun and unrelenting wind, we laboured until there was only one form left. I walked alone to the mound where the rest of CONSTELACIONES awaited holding silence and I laid down the last form on the mound we had created. I sat in front of the mound as the others moved away to gather the sacks of shards that would constitute the final elements of our performance. I sat in front of this mound, in this place of dreams and began to rock and sing the symbol of comfort aloud to the mound. Rocked and cried as I mourned what was lost but also for the joy of the creation of this monument to connection. The wind dried the tears that flowed, the moisture disappearing in the landscape as we, along with the witnesses, closed out our performance to the sound of shards striking the mound. The music of the broken signaling the end and beginning of our Return to Atacama.

Notes

[2] Patricia Verdugo, Chile, Pinochet, and the Caravan of Death (Miami: North-South Center Press, 2001), 133-151.

[2] Doris Dana, ed., The Immigrant Jew: Selected Poems of Gabriela Mistral (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1971), 135.

[3] Patricia Verdugo, Chile, Pinochet, and the Caravan of Death (Miami: North-South Center Press, 2001), 133-151.